The Coal Mines Historic Site, situated on the Tasman Peninsula, is significant to the history of Tasmania as its first operational mine.

Developed both to limit the colony’s dependence upon costly imported coal from New South Wales, as well as serving as a place of punishment for the “worst class” of convicts from Port Arthur, the mine was operational for over 40 years.

Coal discovery

When an outcrop of coal was discovered at Plunkett Point by surveyors in 1833, immediate plans were made by the government to exploit the area. A local supply of coal for the colony was not the only benefit envisaged by Lt. Governor Arthur:

“I think it is not possible that better employ will be found for some of the most refractory convicts than employing them in working coal mines.”

Joseph Lacey, a convict with practical mining knowledge, was sent with a small party of convict labourers to commence the work. The first shipment of coal left the mine on 5 June 1834 aboard the Kangaroo. The Plunkett Point mine was the first operational mine in Tasmania. Prior to its establishment most of the colony’s coal requirements had been imported from New South Wales, at great expense.

The coal was used in households and government offices for heating. Poor quality was a cause of constant complaint:

“The most disagreeable feature attending Port Arthur coals is that when at first lighted they crack and throw out small pieces in great quantities, to the detriment of carpets, furniture, ladies’ gowns etc.” (Lempriere, 1839)

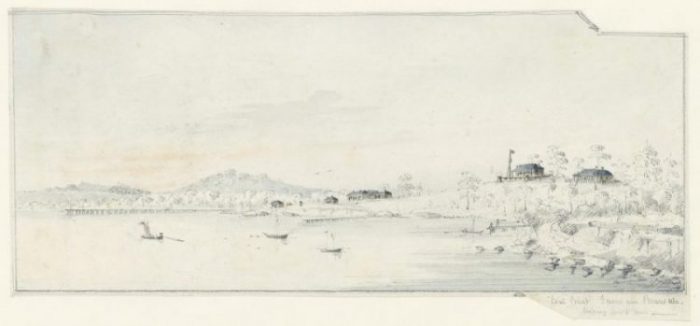

Penal Settlement V.D.L, end of inclined plane and Jetty (Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery: AG1971)

The settlement in 1839

When Lempriere (the Commissariat Officer at Port Arthur) reported on the settlement c. 1839 there were 150 prisoners and a detachment of 29 officers stationed at the mines. Large stone barracks which housed up to 170 prisoners, as well as the chapel, bakehouse and store had been erected.

Today, they form imposing sandstone ruins. On the hillside above were comfortable quarters for the commanding officer, surgeon and other officials. Remains of some of these can also still be seen. Carts ran along rail and tram roads to the jetties for loading.

The coal mines settlement was a punishment station for Port Arthur where repeated offenders of ‘the worst class’ were sent. Besides the men who worked underground extracting the coal, other prisoners were employed in building works, timbergetting and general station duties. Four solitary cells were constructed deep in the underground workings to punish those who committed further crimes at the mines.

A drunken skirmish with the master of the Swan River Packet had nearly cost Lacey his overseer’s position in 1837. He was reprieved after a written apology to Lt. Stuart, the military officer in charge of the station, who had reported him. In 1840 Lacey was sent to Southport to explore for coal in that locality.

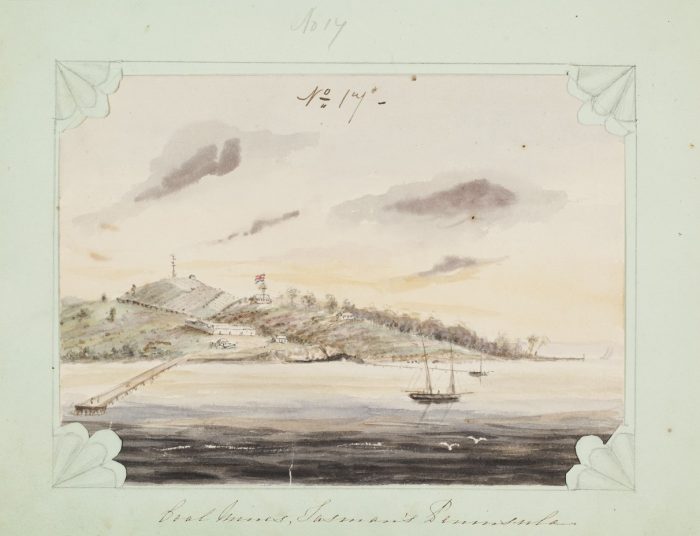

Coal Mines, Tasman Peninsula (State Library of New South Wales: DGA 64 / vols.1-2, FL513694)

Sinkholes of vice and infamy

Under the probation system of the 1840s convicts throughout the colony were no longer placed in private service but congregated in government work stations. During this period the coal mines held up to 600 prisoners.

New accommodation buildings, punishment cells and facilities were built to cope with the influx. The crowding together of so many criminals was cause for official concern. It was believed that they would learn from each others’ vices.

“I have seen congregated at the mines, men of every class, age and station, whether he had been a thief, burglar, deserter, poacher or forger, whether convicted of manslaughter, rape, bigamy, embezzlement, or highway robbery. All were then mixed together, each perhaps an adept in the particular crime for which he was transported from this country, but ignorant of many others, however, after a short period spent amongst such a variety of fellow prisoners, locked up together at night in the huts, listening to their talk and stories of exploit, daring and low cunning and relating deeds of his own past life he soon became identified with them and acquired a knowledge and insight of each different variety of crime.” (Motherwell, 1846)

The incidence of homosexuality amongst convicts at the station also became a major issue. The dark recesses of the underground workings were believed to be ‘sinkholes of vice and infamy’. In an effort to curb such acts additional lighting was placed in the tunnels, auger holes were made in the doors and shutters of sleeping wards and visits by constables were made at irregular times. Over one hundred separate apartment cells were built in 1846 in an attempt to keep prisoners segregated at night. Additional punishment cells were built below, the remains of which can still be seen today.

The Comptroller General reported in 1848 that:

“…great care has been taken to prevent unnatural crimes among the convicts at the Coal Mines, yet from the extreme difficulty of maintaining complete surveillance over the men while at work, the Coal Mines always has been in this respect, the least satisfactory of all the stations.” (Comptroller General 1848)

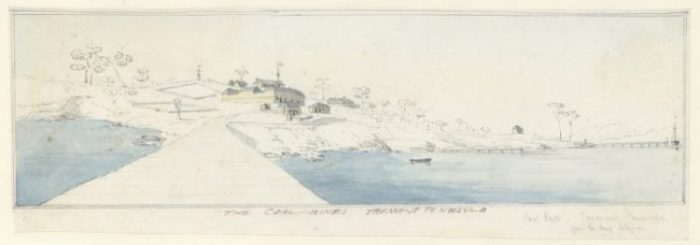

The Coal Mines, Tasman Peninsula, from the long jetty. Martens, Conrad. (National Library of Australia: 3916041)

Coal Point, Tasman Peninsula, looking south west. Martens, Conrad. (National Library of Australia: 577221

At the coal face

The coal at Plunkett Point was first extracted by adits (horizontal tunnels) close to the water’s edge. The coal seam and remains of these early workings can still be seen on the rocky beach below the settlement ruins.

As the workings moved further inland, it became necessary to sink a series of shafts to reach the coal seam. The largest of these was operational by 1846 and can be seen at the top of the hill behind the settlement.

The underground workings were dark, damp and confined. In 1842 David Burn was lowered down a shaft to inspect the mine:

“The winch was manned by convicts under punishment. One stroke of the knife might sunder the rope…however, it has never been tried, deeds of ferocity being very infrequent. A gang on the surface worked the main pump and another below worked a horizontal or slightly-inclined draw-pump which threw water into the chief well…The seam has been excavated 110 yards from the shaft, having also several chambers diverging right and left. The mines are esteemed the most irksome punishment the convict encounters, because he is not a practised miner, and because he labours night and day, eight hours on a spell.” (Burn, 1842)

A steam engine was installed in 1841 to pump water from the mine, making it the first mechanised mine in Tasmania. In the earliest days water was removed by two men with buckets ‘who upon average raised one hundred gallons per hour’.

The convict coal mines were worked by the ‘pillar and stall’ method. Galleries or ‘stalls’ were excavated off the main shaft with thick sections of coal left to act as supporting pillars. Later, as the work of extracting the coal retreated back towards the shaft, the pillars and supporting timbers were removed allowing the roof to collapse.

Hand-driven winding wheels at the top of the shafts were used to bring the coal baskets up from the working galleries. Once at the top, the baskets were upturned into carts for transportation to the jetty at Plunkett Point. This was done via an ‘inclined plane’ (self-acting tramway) carrying the coal from each shaft. The line of the tramway from the main shaft constructed in 1846 is still clearly visible.

Ventilation of the mine was achieved by placing a partition of wood or canvas in the shaft. On one side a fire was lit which heated the air forcing it to rise. Fresh air was then drawn down into the other side of the shaft. Alternatively, two shafts were sunk, with one acting as an air shaft.

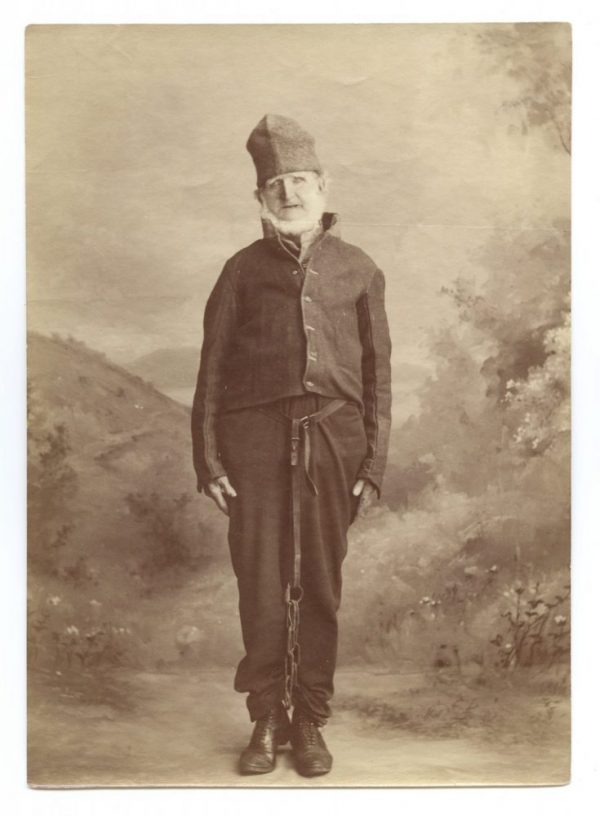

[Bill Thompson], [Hobart : J.W. Beattie], c.1900. (Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania: SD_ILS:616447)

‘An unforgettable scene’

By 1847 the main shaft was down over 300 feet with an extensive system of subterranean tunnels and caverns. The work of extracting the coal was carried out by convicts in two eight hour shifts. The men had to extract 25 tons in each shift to reach the day’s quota.

Reverend Henry Phibbs Fry ventured into the depths of the mine. The scene was ‘unforgettable’:

“I descended into the mines accompanied by Mr Skene, being let down in a bucket, the shaft is 303 feet deep. On reaching the bottom we would have been in complete darkness but for the lights borne by some men who descended with us. We groped our way with difficulty along passages which are said to be five miles in length.

“The roof, in many places, is so low, that we were obliged to creep along the passage beneath it. The air was so confined and damp, that our lamps could with difficulty be kept burning and several of them went out… A few lamps at long intervals were attached to the walls, but seemed only like sparks glimmering in the mist, and not many yards from them the passage was in perfect darkness. There were 83 men at work in the mines when I visited them, the greater number employed in wheeling the coal to the shaft to be hoisted up.

“They worked without any other clothing than their trousers, and perspired profusely. The men in the mine were under the charge of a prisoner-overseer and a prisoner-constable…Having had full evidence of the deeds of darkness perpetrated in the mines, I contemplated the naked figures, faintly perceptible in the gloom, with feelings of horror. Such a scene is not to be forgotten.” (Fry, 1847)

Closure

Charges of inefficiency and bad management at the mines became commonplace in the 1840s. Henry Smith, who was appointed Superintendent of Mines in 1844, proved to be an incompetent administrator. Lt. Governor Denison, himself an engineer, reported in 1847 that:

The works on the shore where the coal is raised are badly managed. Fifty tons only are got out per diem by the labour of 150 men and steam engine, whereas three times the quantity would be raised by private enterprise, with the labour of free men.

(Gov. Denison, 1847)

The coal mines were subsequently closed by the government in 1848 on both ‘moral and financial grounds’.

The convicts were removed to other stations, and the mines leased to private concerns. They continued to be worked, with limited success, until around 1877. The collapsed shafts of the post-convict era can be seen near the settlement ruins. The total output of the coal mines was about 60,000 tonnes.